Victor James Crouch came from a large north London family. After losing both his parents before he was eleven he joined the Merchant Navy when aged 15. By 1941 his home was in Prykes Drive in Chelmsford and in August of that year he married. He had a son the following year. In November 1942 his ship was torpedoed and sunk in the Atlantic Ocean. Victor and his crewmates escaped into two lifeboats. One was found in December 1942 with the crew all alive, but by the time Victor's lifeboat was found in January 1943 Victor and all but one other man had died one by one while adrift.

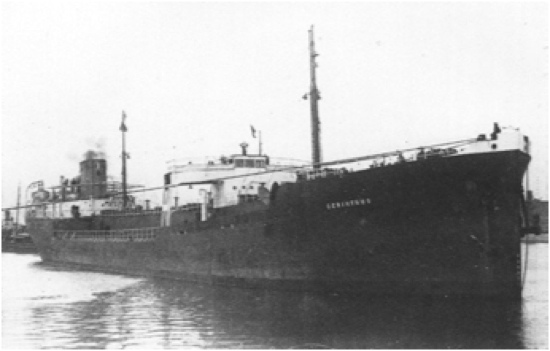

Victor James CROUCH, Able Seaman, S.S. Cerinthus, Merchant Navy

Died in lifeboat after his ship was sunk in the Atlantic Ocean. Aged 21

Victor's name appears on the Tower Hill Memorial which commemorates men and women of the Merchant Navy and Fishing Fleets who died in both World Wars and who have no known grave. It stands on the south side of the garden of Trinity Square, London, close to The Tower of London.

News of Victor's death appeared in a Chelmsford newspaper in 1943:

"For 76 days a lifeboat drifted upon the open sea of the Mediterranean. In it were nineteen men, survivors of the crew of a torpedoed tanker. One of these men was A.B. Victor James Crouch, of 17 Tudor Avenue, Chelmsford. He would have been 22 next month.

When the lifeboat was picked up by an American destroyer only one man was still alive. In the boat were the bodies of the negro cook, and his negro galley boy, who, at 15, had been making his first trip to sea. Nothing is known of the other sixteen.

On a night in November last the man taking the watch on board the oil tanker thought he saw a submarine. One of the officers thought he saw one too. Then it was the turn of Victor Crouch to take the watch. He saw nothing of the submarine until after his ship was torpedoed. It is thought that the submarine, an Italian [sic], came up twice to take the ship's course and speed, and then fired her torpedoes from below the surface.

The lifeboats were lowered. The first one jammed in its davits but all the men, 39 of them, got away safely. They were in two lifeboats, nineteen in one twenty in the other. In a third lifeboat were their supplies of food and water. Then the submarine surfaced. Having questioned the crew, and sank the third lifeboat, it submerged and went off.

For eighteen days both lifeboats drifted together. By that time the men were rationed two ounces of water a day, and a biscuit, The weather was fine and hot. If the wind had been blowing in the right way, they would have made landfall on a small island.

As it was, on the eighteenth day, the Captain decided that the lifeboats should part, to increase their chances of being picked up. One kept on towards land. The Captain's boat, in which was Victor Crouch, made for the open sea. On that day, all the men in the Captain's boat were well. They had even been in swimming to keep cool.

Four days after they had parted the first lifeboat was picked up. For another five days the rescue ship searched for the other lifeboat, and failed to find it. Nothing more was seen of the Captain's boat until it was found on the 76th day, with one survivor, How this one man remained alice can only be wondered at. It is known, however, that when seamen are in such a plight and water begins to run short, they toss up for it. The survivor may have been the man who won the toss.

For 76 days this man drifted. That is almost twice as long as the voyage of the castaways after the mutiny on the 'Bounty' in 1789. Captain Bligh reached Timor after 41 days. That is all we know, so far, of the fate of Victor Crouch and his shipmates.

This story was told to me by Victor Crouch's young wife, one evening this week. She had just finished putting her baby to bed. She heard the story from her husband's friend, Edward Pryor, of Hadleigh, who was on the tanker with him.

Pryor was in the boat which was picked up after 22 days. The two men had been together for several years. When, six months ago, they found they would be on the same ship together once more, they were delighted. but both of them had a premonition. Pryor told Mrs. Crouch that just before he sailed he lost a cross he had always worn round his neck, and he was sure something was going to happen. And when Victor Crouch went out of the house for the last time he turned to his wife and said: 'I've an idea something's going to happen to the ship. But don't you beleive anything you hear about me. I'll come back.'

Just before Christmas Mrs. Crouch heard that her husband's ship had gone down. Now she is doing war work to fill up the days, while her mother looks after the baby. Victor John is six months old. His father came home a week before he was born, and stayed for six weeks afterwards. That was all they saw of one another. 'Another sailor,' said Mrs. Crouch, when she knew it was a boy. But her husband did not agree. He took the baby out every morning. There was no prouder father in town. Now Victor John has only his father's photograph. His mother has given him every sort of toy she can think of. Last week, someone gave him a sailor doll. He likes that best of all.

A.B. Victor Crouch was born at Stanford Hill. His parents died before he left school. At fifteen he did what he had always wanted. He joined the Merchant Navy. He went to most of the biggest ports in the world. His leaves he spent with his wife in Pryke's Drive, Chelmsford. When war came he could have changed to one of the Forces had he wanted, but he did not want.

At Christmas, 1940, he was home on leave. It was then that he met Miss Joan Perry. Before he left for sea again in January they were engaged. The next time he came home, in August, they married at St. Peter's Church. His ship was damaged during the bombing of the docks about this time, so for a short while he worked on the repair of the ship, and they did not go away. Then he went again. The last time he went he thought he should be home by January. On New Year's Day the survivors of the first lifeboat landed in this country. Last week the name of Victor James Crouch appeared in the 'On Active Service' column. And with this verse:

We think we see his loving face, as he bade his last farewell, and left his home for ever, in a foreign see to die. A husband so dear, a father so brave, lies buried in an ocean grave."

Victor’s widow remarried in 1945 and died in 2003.

150311

Victor was born at 1 Stamford Grove East, Upper Clapton, London on 13th March 1921, the son of the gas fitter George Crouch (1884-1931) and Violet Amelia Crouch (nee Osborn) (1885-1925).

His parents had married in Islington, London in 1908, at which time his father was employed as a gas fitter.

Victor's siblings were: George Samuel William Crouch (1909-1909), Patricia Mary Crouch (1910-1998), Margaret Rose Crouch (1912-1993), David George Crouch (1913-1993), Kathleen Violet Crouch (1915-1926), Maisie Lilian Crouch (1917-1996), Eva Myrtle Crouch (1919-2009) and Barbara Joan Crouch (born in 1923).

Victor's parents were both dead by his eleventh birthday.

At the age of 15 he joined the Merchant Navy, the service he remained with until his death.

On 16th August 1941 Victor married Eileen Joan Perry at St. Peter’s Church of the Ascension in Chelmsford.

At the time he was aged 20, a Merchant Navy man, living at 17 Prykes Drive in Chelmsford. His bride was also aged 20, the daughter of Cecil Charles Perry (a manager) and lived at 7 Admiral Road in Chelmsford.

In 1942 the couple had a son. In the autumn of that year Victor was serving as an able seaman on the Merchant Navy steam tanker S.S. Cerinthus (London). The vessel, of just under 4,000 tons and completed in 1930, was part of the convoy ON-141 which left British shores in late October 1942. S.S. Cerinthus' destination was Freetown (in modern-day Sierra Leone).

In the early hours of 9th November 1942 the vessel was hit by one of three torpedoes from the German submarine U-128 about 180 miles south west of the Cape Verde Islands in the Atlantic Ocean.

The crew escaped from the ship into two lifeboats with Victor going into one commanded by S.S. Cerinthus' master James Chadwick along with 18 other men. The other, commanded by the Chief Officer was found by H.M.S. Bridgewater on 1st December 1942 and the nineteen men on board were rescued and taken to Freetown.

Victor's lifeboat and her crew were not so lucky - when it was eventually found on 24th January 1943 by an American merchant vessel only one man, William Colbon, was left alive. The lifeboat had drifted over 750 miles westwards since the sinking of S.S. Cerinthus. The deaths of all the other men in Victor's lifeboat had been recorded as they had died one by one while adrift:

Ernest William Peacock. Able Seaman Royal Navy, died 9th November 1942; Hendry Caddell Aitken, Chief Engineer Officer (aged 58), died 15th December 1942; Leonard Arthur Dickenson, Able Seaman (aged 39), died 21st December 1942; Isaac Yearwood, Chief Steward (aged 66), died 25th December 1942; Victor James Crouch, Able Seaman (aged 21), died 29th December 1942; Harold Ernest Liversedge, Ordinary Seaman (aged 19), died 31st December 1942; Robert Cecil Thomas McClughan, Able Seaman (aged 28), died 1st January 1943; Walter Westbury Jones, Donkeyman (aged 49), died 3rd January 1943; Sidney George Herbage, Able Seaman Royal Navy (aged 35), died 4th January 1943; Bromley William Chilcott, Third Radio Officer (aged 19), died 5th January 1943; Robinson Davies, Cook (aged 42), died 6th January 1943; Leslie William Tyrell, Second Engineer Officer (aged 46), died 8th January 1943; John Jack Paterson, Third Engineer Officer (aged 28), died 9th January 1943; James Chadwick, Master (aged 48), died 10th January 1943; Cyril Ghani, Galley Boy (aged 16), died 11th January 1943; James Boon, Sailor (aged 19), died 12th January 1943; James Henry Grigg, Fireman (aged 20), died 13th January 1943; and Horace Hardaker, Second Officer (aged 28), died 23rd January 1943.